What kinds of challenges or obstacles have you faced as a Native Hawaiian artist? How do you define recognition in the context of your work?

When I started in photography, there was a definite absence of Hawaiian photographers committed to non-commercial critical photographic essays on Hawaiian issues with environmental and political commentary. I am trained as a traditional black and white film photographer and I still work with film and printing archival fiber prints in my darkroom. Consequently, these documentary projects are often seen as controversial by exposing social injustices and because of this are always self-funded. As a second generation contemporary Hawaiian artist, the foremost challenge was for our own people to recognize and accept contemporary Hawaiian art that were not traditional art forms. At that time, opportunities and funding were focused on preserving and perpetuating traditional Hawaiian cultural art practices (and rightly so), but photography was only seen as documenting those practices. For me in the end, recognition of my artwork is about executing my art with: unwavering commitment and consistency of excellence, rigor of research and understanding, rich concepts and content driven by engagement critical to Hawaiian time, place and space and to challenge.

In what ways has your cultural heritage influenced (or not influenced) your artistic practice?

My greatest kuleana (privilege/responsibility) is to be a good ancestor. My great grandmother, Emma KalehuaoMō̄kaulele ʻĀina and her daughter, Janet Kawehilani Landgraf and my mom, Kahulumanu Ahuna Landgraf ensured that for me. Although my great grandmother passed away before I was born, I gained the importance of kuleana, heʻe hōlua (pride of ancestry), hōʻihi (respect) and hoʻomau (resilience). My grandmother was the makahiapo (eldest) of the family and from her I gained the importance of kūpono (just), kūʻē (to resist) manaʻopaʻa (determination) and hoʻokō ʻana (achievement). I always aspired to be my mom and she was my greatest kumu (teacher). She was a naturally gifted and creative artist and I wanted to be just that. From her, I experienced the importance of ʻoluʻolu (graciousness), haʻahaʻa (humility), aloha (compassion), paʻahana (hard-working), maiau (ingenious) and maka lehua (pride in my homeland). Although they have all passed, they are with me always. When my mom passed, it left no generations above me. It was a heavy time because all of a sudden I became kupuna. I kū (exist) because of them. I hōʻauamo (carry on my shoulders) because of them. I am them. I honor and remember them by being a good ancestor.

How has receiving this fellowship affected your development as an artist this year?

The Impact Award played a significant role in advancing my artistic practice, research, and international visibility as a Native Hawaiian artist. Over the past year, award support contributed to the completion, production, and installation of new artwork presented in major exhibitions across Hawaiʻi, the continental United States, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. These opportunities brought Native Hawaiian histories, land struggles, and visual sovereignty into global art conversations—often in institutions where Indigenous voices have been historically marginalized or absent. The award also contributed to critical writing, interviews, and media coverage that helped contextualize and amplify the work for both local and international audiences. This visibility has strengthened scholarly and community engagement with Native Hawaiian contemporary art and expanded the documentation of Indigenous perspectives within art history, photography, and museum practice. In addition to my artistic work, this past year I began a new position as Gallery Director and Curator of Gallery ʻIolani at Windward Community College, Kāneʻohe, Hawaiʻi. With the support of the Impact Award, I have been able to activate the gallery as a space for Hawaiian artists, cultural practitioners, and traditional craftspeople, while also providing public programming—including workshops, panel discussions, and guided walkthroughs—that connect exhibitions to community learning. This expanded role has allowed me to support emerging and established artists and to foster a space grounded in cultural responsibility, education, and aloha ʻāina.

What are your hopes for the impact your work might have into the future?

The Impact Award will support me in honoring and remembering our Hawaiian ʻŌiwi leaders, who have had the moral courage to stand for our lāhui (nation). As a result of the pandemic, we have seen a tragic loss of our Hawaiian people which reminds us of what happened when foreign diseases were transported to Hawaiʻi starting in 1778 with the arrival of Captain James Cook. It has been some fifty years since the Hawaiian cultural movement focusing on Hawaiian language, navigation, sovereignty and reclaiming of Hawaiian land took place. These Hawaiian leaders of that generation are in their 70’s and 80’s, there is a need to record their images and words. And now, we have new generations coming forward in leading our lāhui, but this new generation has not gone through the struggle to gain these rights. We need to capture these histories before they are lost or forgotten. We are in a battle of remember versus forget. We need to remember not to forget.

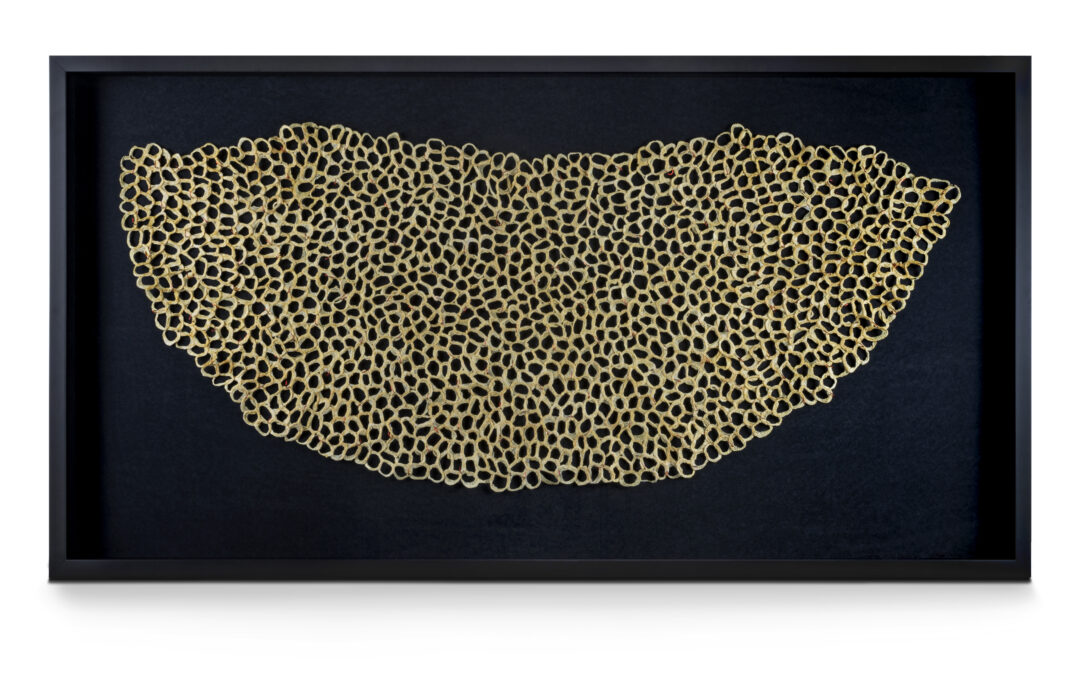

Image: Kapulani Landgraf, Hoʻoheihei, Māhoe Mua 2024, Media: Naʻau (pig gut) with red fishhooks and headless nails. Image courtesy of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge.